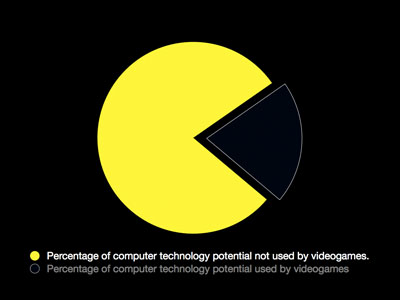

In the wake of The Art History of Games symposium, Tracy V. Wilson’s question as to whether art games are (still) games made me realize that Frank Lantz’s observation that Doom is like rock and roll may hold even more water than I originally assumed.

Maybe we can think of rock and roll as a kind of “hyper” version of traditional folk music that was made possible through technology (electronically amplified instruments and vinyl records). Much like videogames could be seen as a “hyper” version of traditional games enabled by the technology of computers (both as creative tool and distribution platform). Like videogames, rock and roll added a certain vitality and emotional depth to an ancient tradition that totally absorbed a new generation. *

This analogy gets really interesting for me when we start thinking of more extreme or experimental forms of rock music. In the beginning, rock and roll, like videogames, was relatively straightforward and all about fun. But then some people started experimenting and things like The Doors and Velvet Underground happened, followed soon by Sex Pistols, Crass and Dead Kennedys. **

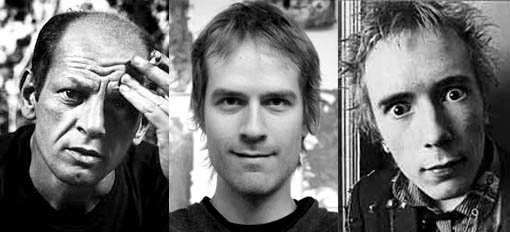

One could argue that the music of Sonic Youth, Psychic TV or Einstürzende Neubauten is as much removed from the “fun” of rock and roll as the games by Jason Rohrer, Daniel Benmergui and yours truly are from the “fun” of videogames. Interestingly, it seems that it is exactly in the deviation that this type of rock (or videogames) starts claiming artistic value. Not only by virtue of not being fun, but also by introducing “alien” elements to the form like noise, unusual structures or narrative content previously deemed unsuitable.

The hairline may be only one of many things that Jason Rohrer shares more with Johny Rotten than with Jackson Pollock.

So rather than thinking of people who experiment with videogames as new Jackon Pollocks or Kiki Smiths, maybe we should think of them as new Nick Caves or Siouxsie Siouxs. They are taking a new technological incarnation of an old analog form and are introducing elements to it that seem to contradict the form’s original merits. And by doing so, they get closer to what is commonly perceived of as artistic.

Next to the more rock-oriented deviations, we may soon be seeing the videogames equivalents of Philip Glass and Michael Nyman and perhaps even Stockhausen or Górecki, as some developers may reject not only the “hyper” version of the form (rock and roll/videogame) but also its non-electronic predecessor (folk music/game).

All this time, of course, rock and roll, as videogames, continues to exist. Once in a while it is influenced by the more artistic experiments. But often it is not. And the two co-exist, appealing often to different audiences, but equally often not without significant overlaps. Sometimes we like playing Mario. Sometimes we immerse ourselves in The Void. Much like sometimes we dance to Abba while other times we need a dose of Cocteau Twins.

* Oddly, there’s a similarity between the two on a social level too. Both traditional games and folk music are often group activities that are mostly about interacting with other humans and having a fun time together. Rock and roll and videogames add a much more explicit notion of authorship to the form and introduce a more severe separation between author and audience, up to the point where enjoying the music or the game could become a solitary activity, thanks to reproduction and distribution technologies.

** Punk is an interesting case because it started as anti-rock and roll but was quickly reintroduced into the mainstream via bands like The Ramones and The Clash who made it fun again.