Knytt, Gravitation, Braid, Everyday Shooter and Zeno Clash. Five independent games. Five times the same experience for me. I launch the game, get to grips with the controls and start playing. Then suddenly, the game stops me. In some cases it makes my avatar die. In all cases, the only thing to do is to retry. And fail again. And retry. And fail again. In some cases I do this two or three times before I close the application (sometimes I uninstall it on the spot). In other cases perhaps 4 or 5 times. But I never made it beyond the first challenge in any of them.

So I ask myself if these games were perhaps badly designed. Some videogames allow you to enter them smoothly and easily. It often takes hours for me to reach the point where the game blocks itself off, closes up like an oyster refusing to give up its pearl. But at least I got a few good hours out of it. Portal was like that for me. So was that remake of Tomb Raider 1. Hm. Does it take money to design a game well?

When I related my confusion to Auriea, she said “You just don’t like games.” That was enlightening! For a moment. I don’t particularly like games. That’s true. I won’t go out of my way to play a game of chess or hide and seek. And I’m not exactly thrilled when my daughter wants me to join her game of Legos or Playmobil.

But.

Those games never end in such a cruel way. When I play chess, I often lose. I’m not very good at it. But I still like playing. When I lose in chess, my opponent wins. And that’s kind of nice. It’s nice to see how my opponent is happy with the victory. And I’m happy for them. But with videogames, when you lose, nobody really wins. And it feels more like the game is designed to make you lose. As if you deserve to be punished for something. When all you did was try to play a game.

If you can call it that!

Outside of the electronic realm, the majority of games require multiple players. As a result, no matter who loses, a human always wins. Electronic games are mostly single player games (even many so-called multiplayer games are expansions on a single player idea). Maybe games weren’t meant to be single player? When I play a non-computer game by myself, the rules are always loose. And when I stop playing, it feels more like the game has lost me than I it.

Computer-based games are like tests. They ask you questions and require the right answer. They make it hard for you, on purpose. They’re not meant to be easy. It’s a format that lends itself to quizzes as well as school exams. Only one of which is a game. Though formally they are the same. What makes a quiz a game and an exam not a game? Purpose! Not its rules, goals or challenges. But its purpose! A quiz is a game (and not an exam) because it is done for fun, because it is not serious (like an exam).

Or is a quiz an exam simulator and considered a game because it’s a simulation, because it’s not real?

The fact that Braid isn’t fun for me does not disqualify it from being a game. It’s perfectly valid to say “This is not a fun game.” What makes Braid a game? Its rules, goals and challenges? No. Because the same format can apply to something that is not a game (an exam, e.g.). On some level, Braid is serious. Like an exam. Does that disqualify it from being a game? Or is the level on which Braid is serious not part of the game? Is Braid an “augmented game”? But what if the level on which Braid is a game is not fun for me? Does it then stop being a game for me?? That’s ridiculous. The nature of something should not change just because of my feelings about it.

Maybe it is sufficient for a game to be fun for someone. Then you can call it a game. Maybe for some people taking an exam is fun. Maybe they would consider it a game too. Maybe it is indeed enough to simply consider something a game. Maybe everything can be a game! You could turn riding on the highway into a game by pretending it’s a race! You could sit in the park and look at the ducks and count their quacks and see if the black ducks win or the white ones. Sounds like a game to me.

So maybe Braid can be a game too?…

Want.

This made me the day.

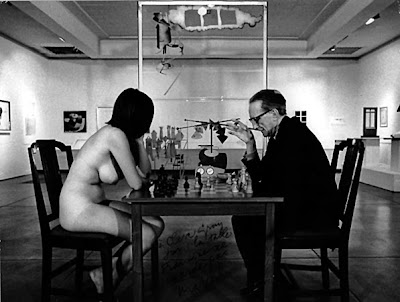

Needs a high-res version of the top right picture. Seriously, what’s going on there? Strip-chess?

Ilia! You should be ashamed! It’s Marcel Duchamp playing chess with a model. In the background you can even see his La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires même.

I think this is a bit pessimistic — when you lose in a video game, you also win since you’ve (hopefully) learnt what _not_ to do! So you might not have accomplished the ultimate goal (winning), but you’ve accomplished a sub-goal, which is learning and improving your knowledge and skills in a way which will make it easier to accomplish the main goal next time.

From this more optimistic point of view, it’s not designed to punish you, it’s designed to teach you how to learn the skills necessary to win!

It just happens that most learning involves some error or mistake-making.

Without goals, it’s not a game; it doesn’t really matter if you never get past level 1, as long as you enjoy playing. Without a goal to provide direction and give you something to attempt, to strive towards, it gets very boring because there is no meaning or purpose to your actions. Goals create the context for everything that happens in the game, otherwise the value system is arbitrary, nothing that happens can be said to be good or bad without some sort of metric to define “goodness”. And a goal provides that metric.

Braid is actually the most forgiving game of all, since it’s absolutely impossible to lose; you just need to rewind and avoid making your previous mistake.

It sounds like you’re simply not learning 😉

Also, I’m not sure that a quiz can really be considered a game — at least not if you define “game” similar to Chris Crawford/etc.

Your insight into purpose being the difference between quiz and exam is awesome! But I think your conception of rules/goals/challenges is misleading.

For instance you’d never consider weighing yourself a “game”, but that has the exact same sort of rules/goals/challenges as an exam or quiz — it’s an attempt to measure something (your weight, your knowledge of X). There’s no intrinsic challenge, the “goal” is to quantify something.

Perhaps you yourself have made up the mental game of “I want to get at least an 80%” or “I’m trying to lose weight”, but that has nothing to do with the actual exam/scale, those are your own self-imposed goals which create self-imposed challenges. As you point out, anything can be a game if you set yourself goals.

Similarly, the use of “rules” with reference to a quiz or exam seems confusing. There are rules in the sense of contest rules — a set of behaviours which are allowed or disallowed — but this seems very different from the meaning of “rules” as applied to a game. The rules of an exam don’t cause anything to happen.. they don’t interactive or generate behaviours. Whereas the mechanics of a game — the rules — generate the dynamics of the game world.

These are all very confusing terms. Makes me feel that it’s not really worth quibbling about whether they apply to anything.

Interesting point, though, about learning. It’s often pointed out by theorists as a prime element in games. I do wonder what all these games are trying to teach us. Only things that apply to themselves, it seems. Which is kind of poor, in my opinion.

But if they’re all about learning, then they should probably be more educational. Simple punishment for mistakes is an outdated concept in any modern ideas about education that I am aware of. Game designers should get a degree in education rather than computer science.

But I have a feeling that these games’ designers are not really interested in teaching you something. I think they know that their audience loves hard challenges. It doesn’t matter how trivial they are. To overcome something difficult is simply something that gamers enjoy.

And I think this is far removed from the multiple pleasures of traditional games. Which makes computer-based games often feel like exams or military drills more than playful activities.

Seems clear to me that Braid is what one would call a “traditional” single player (video)game, providing a very strict division in levels and an iconic reward for each puzzle solved – the piece to yet another puzzle. What tells it apart from primitive videogame masterpieces like Donkey Kong – and so many of the games mentioned in your early list derive from classic game schemes – is the clever (textual) narrative providing significance to seemingly meaningless acts of abstract puzzle solving.

I agree with you Michaël when you say most games resemble “military drills” or “exams” given the traditional rule of making a videogame a challenge requiring coordination – or rhythm, or reflexes, or the ability to memorize, organize or think abstractly (again, Braid falls right into that category). Not unlike a lab monkey playing an electronic game for a fruity reward: the player is not required to think below the immediate and superficial level.

It is hard when you look back to the videogames created so far and realize that a great majority runs on these same principles. Which should serve as a pretense to inflate our praise and recognition of all the hybrids, freaks and abortions that the industry every so often gives birth to.

Possibly games are about the experience of *learning*, not the product of it. They’re about the process of interaction and the way that this affects our minds, which seem to be inherently curious.. we’re wired to enjoy learning. But that doesn’t mean we should only learn in order to know, any more than we should only have sex to procreate!

The process of learning is itself wonderful enough, regardless of whether what’s learned is of any relevance. Even if it was instantly wiped from the brain, we would still want to learn because doing so is pleasurable.

I agree that the only thing you tend to learn when playing a game is how to play the game well, but I think that’s sort of the point — playing the game is a controlled microcosm experience where you’re confronted with a system that you gradually learn to interact with. As you develop mental models, create plans and execute them, you’re learning and it’s stimulating to do so.

The problem with “real” learning (i.e how to play guitar, how to skateboard, how to read) is that it’s not nearly as fun since it takes more time and is much more difficult. Games can give you the same feeling of gratification without years of tedious homework. That’s a small price to pay for the fact that you can’t actually do anything with the skills you may have learnt (aside from use them to play other games).

Of course this limits what they can usefully teach, but that doesn’t matter if what you’re concerned with is the joy of learning.

Playing a game is absolutely like being a lab rat — it’s a tool that lets you tickle yourself! It’s something you expose yourself to in order to produce feelings of wonder or exhilaration or whatever, and if you could simply press a button to stimulate your brain in the same way, you would.

But this sort of behaviour is not at all different than the way that we use music to stimulate our brains! And music is recognized as having the potential to be a sublime, transcendent thing.

No one expects that spending hours listening to music should produce in the listener special skills (aside from perhaps a knowledge of music, or ability to recognize certain patterns, etc). No one demands that architecture teach us anything beyond its own aesthetic and functional beauty. Why hold games to a different standard?

Personally I think the narrative in Braid is utterly useless, as it adds nothing to the *game* — “narrative in games” is as meaningless and superfluous as “music in literature”. Imagine if every book had one of those greeting-card microchips in them, so that while reading the text you would also be simultaneously listening to music. This wouldn’t be seen as a great leap forward but as a needless bastardization of two different works!

See? It’s so low-res I couldn’t tell.

As for Braid, only those who didn’t play the game may think that it has ultimate forgiveness as everything can be rewinded. The later mechanics use things that are immune to time-rewinding. Of course, you can always go through the door and back again to reset the puzzle.

To present it in an easier fashion, I believe if I were to sum up

Michaël’s post, I’d say he was asking: why is there a challenge? He does not necessarily want a challenge. Perhaps I am wrong to sum-up his wonderful blog post in such a shorthanded fashion. There were other points, but this was what appeared to me to be his main point.

But to answer that question, I’d say games need a challenge by definition. Games are fun, becuase of risk-taking to overcome a challenge and complete an objective.

What I’d like to say here to extend on what I said earlier, is that people don’t necessarily WANT a challenge. Is watching a film a challenge? Not very frequently. Is watching a 4 hour arthouse film a challenge? Yes it is, and do you see how many people are prepared to take that challenge on?

‘Games’ has become an incorrectly used term. Games now denote an object of play, which is by definition incorrect. Play is to act or interact. A game is a challenge to complete an objective. The Sims is not a game, it’s a ‘sandbox’ – not in the way we usually mean ‘sandbox’ in games.

And with that, gaming; much like an arthouse film is an acquired taste. Aimed at the competitive teen male. ‘Game’ can create compel and drive ‘play’ or interaction, but interaction or play, most defintely does not always need to be game.

I am preaching to the choir, I just want more people to act on it.

Kyle

( gunpowder )

Your thoughts are important because they relate to the importance of “effort” involved in playing video games, and that effort is obviously what keeps more people from getting into them (starting with you, it seems). But I also think they are problematic, in that “effort” can also be very rewarding in regards to the creative intentions of a game.

First, let me briefly describe the feelings and ideas I associate with the five games you mentioned.

– Knytt aims to evoke the absolute joy of discovering an alien world, and complements this intention by enabling nimble and precise movement through well-designed levels.

– Gravitation aims to communicate the feeling of reaching for “high concepts”, and in some ways needed to be “hard” in order to express this idea through gameplay proper.

– Braid mainly tells the story of someone so obsessed with his own preoccupations that he loses track of everything else, and involves the player in a similar type of absorbing activity.

– Everyday Shooter is all about learning to “play” the game as you would a musical instrument, until you attain some sort of symbiosis with the system. It may be the most self-referential of the bunch.

– Zeno Clash (or at least the demo which I have tried) confronts the player with beings of utter insanity, and chooses to emphasize that encounter through intense physical sensations. It is tough to play, but so is the world it presents.

These games necessitate various degrees of engagement, and are of arguably variable artistic merit. That said, I think that many people could find the effort they require to be very worthwhile, if they get into the right mindset. The work of a designer should then focus on two important things: actually interesting the player in the context and development of the narrative or aesthetic proposition, and then allowing the player to become increasingly confident in his abilities to communicate with the system (that would be the “learning” part referred to above). I think the feeling of progressing within a game by conquering its challenges can be simultaneously rewarding in a personal way and absolutely integral to its themes and “message”.

In your interview with me (I am the guy from Panorama), you suggested that “the public should make a step in our direction”. I understand that you were referring more to the mindset and general state of “openness” that you were asking from your audience, but I also believe this applies to the actual manipulation of a game, insofar as it doesn’t become overly tyrannic. Is Knytt really so difficult that you had to quit the game so soon? Checkpoints are placed at every two screens, respawns are instantaneous, and I believe it to be one of the most intuitive and forgiving platformers of all. If that still doesn’t do it for you the problem might not be so much with the game itself, but in your interest in actually traversing its world. I do think that Braid is way too exhausting (mentally and physiologically) for the rewards it eventually offers, and that Zeno Clash addresses a more specific audience seeking thrills and challenge, but I also believe that a minimal effort of dexterity may reasonably be asked and that a game like Knytt strikes a middle ground pretty perfectly.

When I play The Path, I am engrossed in the act of wandering in an unsettling environment and slowly uncovering pieces of a psychological portrait. The “effort” involved may not be very high, but it does take a lot of time, and sometimes I wish it could just go a little bit faster. Nevertheless, I feel compelled because it feels APPROPRIATE to the thematic and aesthetic material on display, in much the same way that most of these other games find harmony between their content and playability. I do think that more thought has yet to be applied to the ways a game implements difficulty of interaction. But I also think, lastly, that some willingness to engage in a game’s mechanical system and to “train” in applying its rules may be one of the crucial steps to take for non-gamers. We just have to give them good reason to do so…

Your argument is flawed, Kyle. People like games because of their challenge. And they dislike films when they are challenging. Also, the challenge is entirely different: the challenge of games it to learn something that is ultimately irrelevant. Challenge in cinema or literature offers the chance to gain deep insight in human existence.

An “acquired taste. Aimed at the competitive teen male.” is virtually considered barbaric in any other part of culture. Was that the point you were making, Kyle?

Your argument, Louis, loses much of its power when one considers the lack of diversity in the themes of the games you describe. They are all about resolving conflicts not because the authors had something to say about this but because they wanted to make a game and that is all that games can be about. “Game” is a genre of interactive art, like “action movie” is a genre of cinema.

I have learned how to play the guitar and the piano. It wasn’t anything like Everyday Shooter. The piano didn’t tell me I was doing well or not. I did. And it didn’t slam the lid shut when I made a mistake. Also, I knew, going in, that it was going to take me years to learn how to play even the simplest song. And I was ok with that. I didn’t learn the piano for entertainment. I consciously chose to work. And the result of the effort was being able to play the piano, a skill I have been able to apply in many different occasions.

Knytt may indeed suffer from its kinship with other platform games. Through the years, I have learned that these games don’t have much to offer to me. So my patience is very low, indeed. As soon as I recognize the pattern of a certain game style, my enthusiasm drops tremendously.

So I guess I completely agree with your closing comments, Louis, that games simply don’t give me enough reason to go through the training. And that is probably a personal thing.

I’m really grateful to Raigan for saying “if you could simply press a button to stimulate your brain in the same way, you would.” I always wondered about that. And it may ultimately be the reason why I don’t like most videogames. I have never taken drugs. I have no interest in simply generating the “chemicals of joy”. I’m interested in the process itself. And the richness of the experience.

And it was really helpful how you expressed the videogame as an isolated thing that creates its own universe for you to engage in but that, in essence, has nothing to do with anything else (apart, perhaps, from some vague notions of hand-eye coordination). I can see the attraction of that to some people. To a lot of people, in fact. It sounds very similar to pulp literature, for instance, and many comic strips. And I totally applaud it. If people enjoy it, by all means let them have fun with it. I’m all for the legalization of any drugs too. It’s just not something I would do personally.

As opposed to non-computer games. Which include a lot of other ways to have fun and in which training is even optional. You don’t have to be good at hide-and-seek to enjoy the company of other people and the thrill of not being seen. You don’t need to be good at Monopoly to play the game in a romantic way, saying that you’re happy when you end up on the street of your lover and playing with innuendo when you pay her for the privilege. No training involved whatsoever. I wish videogames could be more like normal games.

I’d say that most historians would agree, today, that the first videogame ever created was OXO, a computer version of Tic-Tac-Toe. Take the latter, for instance: a game we’ve all played dozens of times in our life in spite of knowing, first-hand, that it is redundant and devoid of any meaning.

But have you ever tried going back to your school books and see how many of these tic-tac-toe games were played on the corner of the pages with your classmates, just for the sake of abstracting ourselves from the boring matter or making those last ten minutes run a little faster?

Playing videogames is not that different from playing Tic-Tac-Toe. Perhaps players do not realize it yet but, as a habit, it is just as meaningless, redundant, and most of the times it’s not even truly challenging. Personally I also find that the feelings that come after playing most videogames are analogous to those I get after playing Tic-Tac-Toe. I fall into this unshakable indifference, or often ask myself “who won what” and what was it I learned from the experience.

That’s why I hardly ever play videogames anymore. Or Tic-Tac-Toe.

This has been a nice thread of comments indeed. Different perspectives have been presented and the level of depth of this issue would indeed be worthy of spawning many more discussions in the future. Too bad we can’t argue about such issues over a real table with a real pint of beer in our hands.

Dieubussy I think you summed it up quite well for me, I also feel that playing games isn’t leading me nowhere. I listen to Lizst on the piano and my mind explodes in wonderful and vivid thoughts. How many games make you imagine just for the sake of imagining and not for a practical purpose within the game? Which is why I love Ico so much: apart from being a balanced game it is also a starting point for inner search and hours of imagination and delight beyond the game experience. Or for that same purpose, The Graveyard or The Path.

I take it that all the questions you’re posing in this blog, Mr Michaël, are some sort of research for your next game?

Yeah, I was trying to make that point Michaël, that the ‘challenge’ is only suited to a very small demographic.

But then you also brought up that challenging films are insightful, and I guess that is true to an extent. But then I think it was even more flawed, as you say, becuase if I put people in front of a non-game/interactive experience, they ask ‘whats’s the point?’

And they are right.

So objective based play is necessary to drive an electronic experience, otherwise people question it’s point.

But now I am confused becuase a ‘challenge’ comes from the completion of that objective. And therefore anything with an objective is a game. So maybe I am wrong to make the distinction of games being inable to communicate feelings otuside of horror and gratification.

@dieubussy, that’s surely something that CAN change. Once those simple basis for games are contextualised as they are in electronic entertainment, they can start to communicate things and gain meaning. And even when they don’t, aren’t they a form of entertainment? Much like other mediums were initially and still are.

And I know also, that we are from different generations, and I am not worried I may find games a waste of time in the future, but I’d like to know why it is that way.

Kyle

( gunpowder )

Hi Michaël and Auriea, first of all congratulations with the great success of The Path! It seems to getting a massive amount of attention around the world.

Indeed, you can make a game out of anything, it’s relevance or entertainment value will surely be questionable. I think what is putting you off these games is the fact that you are looking for something else to get out of the experience. Maybe the premise of these games made you expect that there was something more than what they delivered?

As a designer myself I recognize the fact that I’m less interested in playing these types of games myself, or at least I do not play them as extensively as I used to. I think this has several reason. Firstly, I analyse them instead of playing them. Secondly, they seems to surprise a lot less then they used to. Thirdly, I think I’m expecting more from them than they can deliver in some cases.

One thing strikes me is in your article is that you are saying that games should be fun in order to be games? Isn’t fun a matter taste? Aren’t you just tired of meaningless challenges? Even chess, which is also a meaningless challenge can’t hold your attention if it were a single player game. The fact that someone else wins seems to make the experience bearable, and it comforts you to know someone else enjoy winning.

What I’m saying is, aren’t you looking for a different kind of fun? Inspiration, wisdom and thought provoking fun? This should surely be not a problem for Tale-of-tales’ games? Which reminds me, I still need to play The Path (hides in shame.. 😉 )

I’m afraid I’m not nearly that efficient, Demi Tasse Spoon, that all of this is research for a specific project. I just have these questions popping up in my head. And it really helps to share them with you.

As you know, I consider the differences between traditional games and videogames to be very important. But most of my colleague game designers don’t agree with this. They see videogames as just another way of making and playing games. I understand and respect that, but lately I have started the realize that their work is seriously lacking compared to non-computer-based games. Computer games, especially these more hardcore indie designs, seem like traditional games but stripped bared from anything but their rules. If you ask me, it’s the difference between a fun social activity and filling in a tax form on your own.

It’s true, Tj’ièn, that I look for a different kind of fun in videogames (I’m personally not even all that interested in fun social activities). But if we’re talking about the fun to be had from actual games, I don’t see computer games competing successfully with even the simplest of traditional games, like Tic-Tac-Toe. They are so self-obsessed, so strict, and so barren. I’m wondering why we don’t let the computers play these games already. Because that seems to be the perfect audience for them.

I’ve often come to the point where I see the value of an indie game but don’t feel like playing them because they’re inconsequential. Take OSMOS (I think that was the name) for instance. It’s brilliant, simple, stylish… and yet I got tired after 5 minutes.

What makes me want to play a videogame, apart from the novelty, is the same thing that drives me to the theatre or to a book: I wish to unveil its narrative, expose its “characters” and after that I might feel fortunate I did go that play or read that book. So I disagree with Raigan who denied the power of narrative in videogames.

Braid is better than most games not because of the licensed soundtrack or the cute graphics: but because it ads narrative and makes the puzzles intertwine with a very introversive story of a fictional character facing all those challenges. Most people, I suspect, don’t bother to read the text before each level so the miss the whole point.

In the end nothing beats doing something with other people. Computers are a poor substitute at that. I had more fun the other day playing five minutes with a simple balloon with my family, out of the blue, than I had playing videogames in 2008. So even the “fun” factor seems to have gone somewhere else in today’s videogames.

This is all very intriguing I must say. When playing these so called real games the activity is mostly not about the game itself, but rather it provides a context for social interaction. And although computer games traditionally are not developed like that, they can do that. Lots of my friends play Singstar much as they do Settlers of Catan, both provide a context, an environment for discovering each other.

Naturally, single player computer games can’t come close to this, as you need friends playing along. So we shouldn’t want them to provide the same kind of fun. Computer games have for the most part be about themselves. They are created so the player can learn them and eventually complete them. If these computer games want to come close to the experience of playing “real” games then they should start to focus on the player and provide a context where the player can discover him- or herself.

I firmly believe that this is possible, but I do not think we have gotten really close yet.

The thing about games is that they’re not meant to be efficient. For software other than video games, the user failing at achieving a task would be considered a design error; in the case of games, it is just part of the aesthetic of the communication between player and game. It is true that challenge has long been a game design cliché, and that all games need not be challenging, but expecting every game to be challenge-less is making the same mistake, just on reverse.

Also, are you sure that every game should be designed for the enjoyment of its player? Isn’t frustration a valid aesthetic response? Games like I Wanna Be The Guy use challenge in this fashion.

I totally agree that games don’t teach valuable lessons today! Just as Chris Crawford said. In the case of Braid, I believe they are very stimulating challenges, though.

By the way, that black against red provides very poor contrast for comfortable reading.

(The background colour of this website is different every time it loads. So just reload the page if you can’t read it well.)

Agj, we are not looking to change “all” games. We are just trying to understand how people enjoy certain games and looking for other ways to enjoy them, or creating other games to be enjoyed in different ways.

Tj’ièn, I wouldn’t give up on single player games so easily. We shouldn’t forget how powerful computers are! Most videogames still treat the computer as a framework, a system that represents the rules and an arbiter. But what if we start thinking of the computer as a partner, as an equally active party in the inter-active process that a game is supposed to be?

Not simply as an opponent -we can still make single player games (I actually think this is one of the advantages of videogames)- but as an entity (or multiple entities) that is there, a life form that is present in the game (it doesn’t even need to be a character, it can be a place too, e.g., or a general “presence”).

This would not produce the same social fun as traditional games. But it could enrich the play activity, perhaps to bring something new to the table, something unique. In fact, this already happens, once in a while, in videogames. Just not very consistently and few games have been built on this premise.

I think the majority of single player games I know feature the computer as the opponent, enemies, level bosses and obstacles; but also a helping hand like tutorials, hints, or even computer controlled partners (that end up being hazards due to poorly implemented A.I., true).

When I read your description, Michaël, I was instantly reminded of the girl in a white dress in The Path, the one that plays around with you and shows you the way back to the road – hand in hand. That was one of the richest concepts featured in the game: neutral, unexpected and filled with a life of its own. So precious.

@Kyle – yes they are entertaining but I’m through with “just” entertainment. I’ve been entertaining myself since the 1980s. Videogames, being a part of a larger medium, have little evolution to show for in the fronts I wished them to evolve the most. They may even have gotten worse than they were years ago. Still I don’t give up.

Moreover, I believe you don’t really need to come up with some radical and highly inventive game concept to triumph in the creation of a videogame. Take our two favorite games (laughs) for instance. It all boils down to a question of good taste.

I’ve been entertaining myself since the 1980s.

This made me laugh out loud. 😀

I think there’s two main directions for the evolution of videogames. And both are equally valid. The first is The Nintendo Path: move closer to non-computer games and try to (re-) capture what is fun about them. The second goes in the opposite direction: move further away from games and evolve into a rich and diverse artistic medium. I hope both will happen because I like both and most games today are too little of either.

As if this subject wasn’t complex enough already, you had to bring Nintendo into it…! 😉

Yeah, I think the point is, it’s not financially viable to create these artistically diverse games anyway.

This industry is in a rut really. Indie is the only way forward, if these artistically rich experiences are to be continued. And it’s all too infrequent we hear of some VERY lucky developers being given creative freedom and limitless support.

It should be happening with first parties MORE, and for third parties it’s left exclusively for the classic PC developers, or the likes of Kojima.

Anyway, summing it up like that, makes it all seem so pointless. Why do I even want the medium to be an art? Is it so I can justify wasting my day away playing them? I’d like to think frequently, it’s because I learn something from them, but they are VERY rarely that deep. And we are almost always discussing games critically, rather than objectively or observantly.

And dieubussy, I assume you have not been on the forums recently, but Red has left, and TIGmagazine is closing. So we only have the community blog now, but nevermind.

Kyle

( gunpowder )

To Kyle (off topic): I checked the forums just now and indeed it is sad. But I’ve seen Red part and return a few times.

There’s a considerable number of recorded cases in the history of videogames where artists invested in important projects, trying to come up with fresh and inventive ideas. Such was the case of studios like Tribecca or authors like Toshio Iwai, Russ Lees, Peter Gabriel, Thomas Cheysson, Mike Oldfield, Ryuichi Sakamoto and many others. They all created (or participated actively in the creation) of relevant games: I would go as far as to say that some were truly memorable. Yet for some reason most of these luminaries didn’t feel like going back into videogames after their first exercise(s).

So yes, Kyle, I also think that unless the perfect environment for the creation of visionary games is available, it might not be rewarding enough for the designer – as I stressed some comments ago. Which is a shame once we realize that videogames have this unique way of relating to the player that begs to be explored further. Ultimately it’s the industry, more than the medium itself, that’s rotten from the inside.

Now if you’ll all excuse me, I’m off to play the latest Maki D.

The solution is very simple, though. It’s longer term thinking. Big game companies should invest in experimental games production now so that they can access new audiences when the current narrow marketing segment of gamers has become fully saturated (soon). The fact that they don’t do this proves that they are not committed to this medium and absolutely worthy of all the disrespect bestowed upon them.

So it looks like only we (the people who care) can prevent this medium from falling into an abyss, from being forgotten, abandoned. And if there’s no money in that (though I’m sure there could be), then we just need to find a way to do it without money. This work is too important to be stopped by capitalism.

I think it really comes down to different games for different people. Some people like the jump-though-endless-hoop games, some do not. What I find fun are games like The Path, Myst, and the old text-based adventure games — basically games where you can learn by exploring rather than being just another salmon swimming upstream to your eventual demise. I also enjoy games like Bioshock and Half-Life 2, but the whole time I am playing them I keep thinking — why do I keep having to shoot people, its getting in the way of the story! The problem here is that the whole industry was developed around hoop-jumping games, and so developers think that if they don’t cater to this market, than their games won’t sell. Hopefully The Path will lead the way to developers making games for the rest of us!

I completely recognize what you’re saying, John. Sadly “developers think that if they don’t cater to this market, than their games won’t sell” is probably true to a large degree. But only as a self-fulfilling prophecy. The more they cater to the same market over and over again, the harder it becomes to reach out.

Because people “on the outside” continuously get their opinion/prejudice confirmed that games are not for them. So when you then finally do make a game that is for them, first of all it’s hard to reach them (when they have learned to ignore video game news) and you have to convince them to spend money on you (when they had already decided never to buy games).

I’m absolutely convinced that there is a gigantic market out there (much bigger than the current gaming niche) for new types of games. But, to some extent, the games industry’s commercial success within the niche, makes it harder to reach outside (and therefore easier to give up on such attempts). As a result we need massive marketing for extreme experiments. And that probably sounds like a contradiction to people concerned with commerce.

Michaël, ultimately that is an assumption. I don’t know if there ARE that many of us that play these ‘games’, or how many there potentially are.

Of course I don’t want to offend you or John Ludd, but I disagree about ‘The Path’ being fun. For me it was NOT fun. But I didn’t go in with the expectation of something that I would waste some time with, that would pass time in a fun manner liek tic-tac-toe. I went in wanting to play it, to experience something different. And it was not fun. It was a jarring and uncomfortable experience, intentionally so. And it made the moments of ‘relative’ harmony, seem much more potent and comforting.

I am no intellectual, and I am sure, I am sure I am not doing it a great service by brushing over the experience in such a general fashion, but I don’t think there is a market for this. People play games for a fun waste of time. That, I guess, is a fundamental problem.

What does need to happen, is that there needs to be more government funding programs to support indie developments. Or more opportunities for grants for interactive arts.

We shouldn’t expect the likes of EA and Activison to shift focus, especially given how unpredictable the industry is at the moment.

It is something platform holders can afford to do, too, so some initiative on their part would be great. Sony is hit and miss, with some great opportunities, and Microsoft has the XNA, but neither of those are consistently useful to the projects that need help. Mainly becuase XNA suite is very basic, and from what I have heard the PS3 is very complicated to develop for. And PC isn’t a platform that can support these things.

I don’t know. I just want to see more opportunities. And for the sonsumer side of me, I want to see more opporunities beign taken advantage of by indie devs.

Kyle

( gunpowder )

@Dieubussy, I was saying the exact same thing. But not to him. I think he gets complacent very easily and I expect he will be back too.

Good he’s taking a break though.

Kyle

( gunpowder )

I am totally on the same page as you. I absolutely *hate* when a test pretends to be a videogame and it happens all the time. You’re doing great work here! Keep it up.

I can’t say I understand the phenomenon, but I’ve started to notice that there are a lot of people who get really frustrated by difficult games, and I don’t think it’s as universal as some are making it out to be.

I think the comparison of exams to quizzes has the answer. An exam isn’t fun because so much is riding on it. If you fail there are very real consequences with ramifications for your entire life. If you fail at a trivia game though, it’s no loss. At the very worst you will look dumb.

The key thing here is that it’s all in your mind. You could have fun with the questions in an exam if there wasn’t so much riding on them. The thing with a game is, there really shouldn’t be any pressure. I mean, nothing bad happens if you lose. You just don’t get to advance.

I think that a lot of gamers, the ones who enjoy hard games, don’t feel bad about losing. They’ve internalized the notion that “it’s just a game” to the point where there is no losing, only winning and learning experiences.

I guess that not getting to advance could be a big enough penalty. I certainly wouldn’t want to continue playing a game where I wasn’t getting anywhere. And it seems pretty pointless to pay for something you mostly aren’t going to get to play, so I see where some more practical pressure would be involved.

What I’m trying to say is, at the very least, the games that bother you seem to be not so much bad as they are interesting to different players. Players concerned less with where they are going and more with what they are doing.

True, shMerker, but these players who do enjoy these games, tend to be better at them as well. If they would fail as much as I do, I’m sure they would give up too. Computer games are only fun if they make you feel smart or skilled. If they make you feel stupid and clumsy, you might as well stop playing, especially considering that you were just doing it for fun in the first place and there is no other reward in them.

Gamers are just good at playing games. And that makes all the difference. At least for (single player) computer games.

So it’s not just that they like to be frustrated. It also that they overcome the game’s challenges much more easily. So they experience a lot less frustration to begin with.

I think you missed the whole point in braid.

Press X to rewind time, and learn from your mistakes with no added consequences like “dying” or “failing”.

Too bad that this can’t be applied in real life, or you could have rewinded time and never have written this flawed and ridiculous article, because it only shows you have absolutely no understanding of ludology.

Oh wait, perhaps you can. It’s Da Internetz after all.

While you do that, don’t forget to delete your comments as well, because comments like “the challenge of games it to learn something that is ultimately irrelevant. Challenge in cinema or literature offers the chance to gain deep insight in human existence.” only shows you don’t understand that games (or at least games with narrative, like the aforementioned Braid) offer you both kinds of challenge: Practice a (perhaps) irrelevant skill in order to pursue a (perhaps) irrelevant goal (like saving the princess) *AND* gain deep insight on human existence.

If you are having trouble surviving in Knytt and Braid, then you are either unusually slow-witted or spectacularly clumsy, or both. Knytt and Braid are both extremely forgiving. There are very few serious threats, and if you die, you lose at most a couple seconds of game time – so little that it’s almost misleading to say that you ‘died’. Not only that, but you don’t even have to solve any the puzzles in Knytt or Braid to progress through most of the levels. Heaven help you if you try to play Super Mario or Pacman. I guess those aren’t games either?

Also, of all people, you question whether Knytt and Braid are games? You, who make little semi-interactive tech demos and try to pass them off as games? Now I understand why you design them like that: you design games you want to play — but you’re not skilled enough to play anything with the slightest bit of challenge or complexity.

Let’s just say I have a different set of skills, shall we, David?

I’m always surprised by how unaware (skilled) gamers are of their own talents. It really doesn’t help to tell me that game X is almost too easy when I just spent hours trying to get through its first challenge. I don’t think I am particularly stupid or clumsy. I think gamers simply have a specific talent and set of skills that makes this stuff easy for them.

But in the end, it’s probably just a matter of what you find pleasant to experience as a human. Some people like overcoming challenges in rules-based systems, others prefer sitting in the garden watching butterflies in the wind.

I have to agree that the idea of death or failure in a video game is a trend that needs to…well, die. It detracts from so many aspects of the game, especially the story. It’s made even worse when you’re not allowed to save your game anywhere you want. That’s one of the many things I’ve complained about excessively.

But honestly, Braid? Really? Even if you’re not great at jumping puzzles, you have to admit that the ability to rewind to exactly five seconds before your fatal mistake is pretty good at reducing frustration. Granted, the rewinding ability doesn’t help much if a puzzle is ridiculously hard, and it’s still an “exam-style” game at the core, but you have to give J-Blo credit for that.

I was very hopeful for Braid because of this feature. But I think Mr Blow has, in a way, designed the game too well. The wind-back feature is not just a gimmick or an “undo” function. He has actively incorporated the mechanic in his design of the game, which is highly appropriate as a design choice. But it puts me, as a less talented player, back at square one.

Maybe this is where the key to this conflict lies. Computer games are just much better designed than traditional games. Or at least much more thoroughly and consciously. While the design of other games -go, tag, tic-tac-toe, etc- seems to have “grown” throughout the ages, perhaps simultaneous with man’s ability or desire to play them. Perhaps computer games are to “normal” games what modern literature is to folk tales.

>> you have to admit that the ability to rewind to exactly five seconds before your fatal mistake is pretty good at reducing frustration.

One of the wonderful things about Braid is how this function, which initially seems like a miraculous convenience, immediately becomes a gateway into a higher-level set of problems that are much more challenging than the ones it solves. There’s something profound and funny and sad about this tiny expression of the dialectic of enlightenment. This is the kind of beauty that Michael has no taste for. Which is fine, no one is under any obligation to like games.

On the question of what a game is and isn’t, the work of Wittgenstein – a brilliant and radical philosopher – is full of insight…

“Consider for example the proceedings that we call “games”. I mean board-games, card-games, ball-games, Olympic games, and so on. What is common to them all? — Don’t say: “There must be something common, or they would not be called ‘games’ “-but look and see whether there is anything common to all. — For if you look at them you will not see something that is common to all, but similarities, relationships, and a whole series of them at that. To repeat: don’t think, but look! —

Look for example at board-games, with their multifarious relationships. Board games, what are some? Consider chess, of course, but think also of monopoly.

Now pass to card-games; here you find many correspondences with the first group, but many common features drop out, and others appear.

Card games. What about poker? And what about Old Maid. Remember that children’s card game? How are these card games alike and different from each other? And how do they compare with board games? What about the element of strategy? Or how many players can play and whether or not there is a single winner or, as in Monopoly (I believe) there are different degrees of winning.

When we pass next to ball-games, much that is common is retained, but much is lost.– Are they all ‘amusing’? Compare chess with noughts and crosses. Or is there always winning and losing, or competition between players? Think of patience. In ball games there is winning and losing; but when a child throws his ball at the wall and catches it again, this feature has disappeared. Look at the parts played by skill and luck; and at the difference between skill in chess and skill in tennis. Think of the way one wins or loses in tennis. Winning is hierarchical. One can win a point, but lose the game. One can win the game, but lose the set. And one can win the set, but lose the match. One can win the match but lose the tournament. Compare this with baseball (also hierarchical) or with checkers. And howabout board games that revolve around a throw of the dice?

Think now of games like ring-a-ring-a-roses; here is the element of amusement, but how many other characteristic features have disappeared! sometimes similarities of detail.

Then we have children’s ritual games. Do they have a winner? What about drop the hankerchief? Or London Bridge is falling down? How about “spin the bottle.”? Are you winning or losing if the bottle stops pointing to you?

What about jacks? Jacks is a girls’ game that was popular when I was a child and I was into the game. You have 10 little objects called “jacks” that you toss onto the ground as the other girls sit in a circle. Then each girl has a turn. She starts with a ball in her preferred hand and she tosses the ball up and lets it bounce and before it bounced again, she picks up one jack and then catches the ball before it bounces again. She does that with each jack. Then she does “twosees” which means she picks up two jacks in one sweep. She continues that until she has done all ten jacks. Then, if she completes that round without difficulty, she starts again with a more difficult rule. Perhaps she doesn’t let the ball bounce at all, or she not only picks up the jacks but she puts them in a particular place before she catches the ball. There are a few of these rounds that are already invented, but it is common for the winning player to invent the next game.

How does “jacks” compare with chess? Or with ring-a-ring-o-roses? How are they different? How does it compare with tennis? Or American football?

And we can go through the many, many other groups of games in the same way; can see how similarities crop up and disappear.

Don’t children invent games on the spot? See who can spit the furtherest? Or see who can solve a particular puzzle first? Or who can follow a rule the best (think of Simon Says).

And the result of this examination is: we see a complicated network of similarities overlapping and cries-crossing: sometimes overall similarities.

And what you’ll find, I think, if you go through a careful study of these various types of games, is that there are similarities and differences. Poker is like chess in certain ways. They both have clear rules and the winner is likely to have practice and skill. But they are different in some ways, too, and if you look at how they are different, you’ll find other games that are not different in these ways, but different in other ways.

I can think of no better expression to characterize these similarities than “family resemblances”; for the various resemblances between members of a family: build, features, colour of eyes, gait, temperament, etc. etc. overlap and cries-cross in the same way.-And I shall say: ‘games’ form a family”

No definitions, no essential features, just games as the things we call games!

What about card games like Solitaire? One Player, a win condition and a lose condition, and it’s even more punishing than many computer games because the “difficulty” is randomly computed at the beginning of every round. The “game” in solitaire is figuring out which order the cards are in, and the “game” in Braid is figuring out how to exploit the systems of the game. For me, Braid was a brilliant example of taking 5 different systems and fully exploring every possible use of them for game play. You can’t call it a test, because of the purpose of a test: to demonstrate previously known knowledge by showing it again. In Braid, the game is figuring out that knowledge, but once you know it you’re on to the next puzzle. You never do the exact same thing twice, it’s always a more clever and different twist on the same thing. I feel like the same thing goes for Portal. There are definitely games which have “puzzles” that are purely tests of previous knowledge, Half Life 2 has many of them, but there they are used tastefully to help you out. If you are approaching a charachter you can kill by doing something specific, then refreshing their memory with a “quiz” in game is a great way to do it without that punishment of death if you fail to do it correctly under pressure. An example of this is in HL2: Episode 2 with the mine cart that you can roll down the mineshaft. While I agree with you that games that are pure tests are not fun, I feel that the games you mentioned (excluding every day shooter which I haven’t played) are not really tests, more tools for figuring out the right answer. Also I feel that tests really do have a place in game design.

This was mildly interesting, but you stopped just as you were getting somewhere in your analysis of games. It deserves more rumination with less preamble. That’s why we write our thoughts down, so we can distill their essence and creatively sort our ideas in a cogent manner, in order to present them more effectively to other people. Call it a game if you want.

That’s not why I posted this, Michael. I wanted to hear the reactions of other people. I have no answers. Only questions. But the comments here definitely brought me closer towards understanding something that is, basically, alien to me.

This post is part of a long series that will undoubtedly continue. A series in which, amongst other things, I am looking for an answer to the question what it is that makes computer games different from other games. And the sub-questions of why do many gamers resist the notion that they are.

OK, while this is all an interesting general field of thought here, I have to point out a basic flaw in your logic here. To briefly paraphrase, you suggest that the difference between [most] tabletop games and [most] videogames is that with the former, by the end of the game, someone always wins. As opposed to a videogame, where more often than not, for you at least, the game ends with you getting frustrated and shutting it off.

If the point at which you throw up your hands and declare you quit qualifies as the game being over for you, then the exact same problem applies to any game. I’ve rarely seen a game of Monopoly played for instance where no one ever quit out of boredom or frustration. If we eliminate every situation wherein a player gives up on a game and stops partway through, there does not exist a single-player videogame that can be won, where players of that game will not have won by the end of the game, period.

Now, going from earlier comments here, there are two points I see cropping up repeatedly. That people who seriously play a lot of videogames have developed a skill set which allows them to easily breeze through games, and that the skills one develops by playing a game do not help in any situation beyond playing that game. The first of these points, which is absolutely true, disproves the second.

If you play a game, of any sort, whose outcome isn’t simply luck-based, you will develop useful skills. If it’s a puzzle game, like Braid, or Myst, or a jigsaw puzzle, you are honing your deductive reasoning and general problem-solving skills. If it’s an action-intensive game, like a shooter, or darts, you are improving at the very least your hand-eye coordination, and most likely some higher level math, calculating on the fly where and when to shoot to properly intercept a moving target.

More to the point, these are skills that anyone who is physically capable of playing these games can and will develop if they don’t give up and walk away. The only difference between you and the people you are arguing with that let’s them finish a given game while you don’t is that they don’t give up as easily as you do. Heck, personal anecdote. When I was a very young child, I suffered permanent irreparable damage to my nervous system due to an untreated case of Lyme disease. It took years of therapy for me to be able to write, speak clearly, tie my shoes, or really do much of anything, and to this day I’m only able to perform any physical activity half-competently, requiring a fair deal of concentration. Even with severely impaired motor skills however, I am better at most videogames than most people I’ve ever met. Quite frankly, the practice it took to attain these skills was good physical therapy, and the results a boon to my self-esteem.

While I’m rambling here, the whole issue of learning to play a musical instrument vs. learning to play a videogame is an interesting one. Again, as laid out earlier in the comments, it’s not a functional metaphor. If I’m playing, say, Super Mario Bros. and I hit B when I should have hit A, I’m going to fail to properly get through the level on that attempt, or at least deal with the personal frustration of doing so in less than optimal fashion. If I’m playing an arrangement of the 1812 overture on the piano, and I hit B when I should have hit A, I’ve ruined my performance of that song, or at least I have to deal with the fact that I’ve played it improperly.

Now, you might argue that the game will make me start the whole level over, while I can still muddle through the rest of the song, but that’s really not globally true. If I’m recording the song in a studio, or constantly botching a rehearsal, I am indeed going to have to start over, or at least backtrack some. Meanwhile, on the other end of things, the general degree to which games forgive errors has been increasing over the years, to reach a wider audience, and hopefully it’s a trend that will continue. The most recent Prince of Persia for instance is very remarkable in how quickly it brings you back to the moment before you make any mistake, with nothing but a quick hand-clasp on screen as a record of your error. Alone in the Dark 5 meanwhile has an actual feature built into the game (albeit with some arbitrary restrictions) allowing you to skip directly past any given segment of the game you find too frustrating to finish. While personally, I’m not inclined to make use of such a feature, it is something I would love to see all games implement in the future.

Skipping game challenges sounds like a great idea. But of course it can only be successfully implemented in a game that has something else to offer than challenges.

Just to be clear, I never meant to refer to table top games exclusively. I’m interested in the difference between computer games and traditional games. Most tabletop games are very recent inventions. And I imagine many of them have in fact influenced computer games (and vice versa, these days).

Anyway, you’re perfectly correct. People do learn things from any sort of games. But different people value these things differently. Some people think hand-eye coordination is a wonderful skill. Other people prefer to gain insight in certain emotions or learn about new ways of looking at reality.

The former will be perfectly satisfied with computer games. The latter not so. We’re very happy for those people who are happy. But please allow us to pursue our own happiness.

Your computer games do not make us happy.

Well, just to disambiguate things a bit, when I say “tabletop games” I more or less mean “any game you play with people sitting around a table, vs. a computer/console.” Someone can get fed up with Chess or Go just as easily as any given videogame. For that matter, I’ve seen kids quit in the middle of games of tag, or hide and seek, and just wander off.

The point is, having challenges to overcome isn’t just an aspect of games, it’s more or less what defines them. A game is a challenge, against other parties or against yourself, to see if you can accomplish some goal with some set of restrictions, generally for the purpose of amusement.

If you try to strip that out of a project and call the result a game, you’re abusing the term. It’s like if I were to say, “I hate having to read. Many people are illiterate and can’t read at all. I’m going to write a novel that doesn’t involve any reading.” I might then go on to create a book filled with 400 beautiful illustrations, and that would be great, but it wouldn’t be a novel. It would be a collected series of illustrations. That’s a perfectly fine thing to create, but if I then ran around declaring it was a novel, and responding to people who corrected me that War and Peace isn’t a novel because it didn’t appeal to me, I wouldn’t really have a leg to stand on. We get into the problem here that there isn’t really a term for an art project created with a toolset usually used for creating videogames. Explorable Virtual Landscape maybe?

I’d also say there’s merit to being able to skip over parts of a game you aren’t up to whether or not there’s more to the game than the gameplay too, really. To make another metaphor, if I have a book full of various word puzzles, and I can’t stand doing the jumbles in it, I might still want to skip around and just do the crosswords.

But wouldn’t it be a very poetic and potentially beautiful thing to make a book that consists only of pictures and insist that people read it as a novel?

I’m not saying that that is what we do at Tale of Tales. I’m saying that part of any artwork is to make you see things in a different way. To make you look at things in a way you may not be used to.

A game may be a challenge. But I’m sure that some people could call just about anything a challenge. And a challenge is not necessarily a game. In terms of semantics, I’m on the side of Wittgenstein quoted above: game is a very loose term that can be used for many things. Let’s embrace that and make many different computer “games” too!

Well no, your stuff (with the possible exception of Endless Forest anyway) is more about minimalism on the actual gameplay elements, with a lot of focus put on the overall aesthetic presentation. The Graveyard for instance fits my definition of a game, and it honestly is conceivably possible to get stuck. The argument can be made that it’s all one big puzzle. What is there that I can actually do here besides just walk around? Granted, if you hit escape, it’ll come right out and tell you, go sit on the bench, then leave.

Now, if there was no bench, or way to leave eventually leave, we have eliminated the ability to hit a point where you potentially won’t be able to finish the game, but we’ve also eliminated the ability to call it a game. It’s just, a nicely rendered graveyard with an old lady you can make putter around. Interesting little toy, but all there is to do is fiddle around with it until you get bored, then leave.

Really, there’s always going to have to be SOME form of challenge or goal to still call it a game, and the possibility will always exist for someone not be able to work that challenge out at first. I used to hold up Shade ( http://www.eblong.com/zarf/if.html ) as a great example to use if you needed to explain to someone the unique way in which a game can provoke emotional responses in ways other media can’t, but then I found out that, simple as it is, there’s still a fair number of people who can’t get through it. It’s all just a question of how much difficulty you’re willing to deal with, and how little difficulty leaves you bored.

As long as something has rules and is intended to be enjoyable for at least one person, it is a game. It’s definition, to me, is very similar to that of art.

That being said, it is impossible to make a game where the player cannot fail, where the player is protected from that feeling of frustration you had while playing Braid. Obviously you can do things to scale a game, making it more difficult or easier, but in the end, by definition, there are things that the player can do that will not progress the game.

In Braid, this can mean not solving a puzzle. In Super Mario Bros., it can mean not knowing how to jump over that first Goomba. In tag, it could mean just sitting there.

I think a lot of your frustration comes from your expectations. It feels, from reading this, that you expect to play a game and win, and that you view failure as not only a bad thing, but a personal attack.

I have a wonderful girlfriend of 4 years, and when I met she was not interested in games. Now she is indeed someone I would call a gamer, and it has been very interesting for me, as a designer, to watch her growth. I have seen her slowly change and picked up on some of the ideas that go through the heads of people at varying stages of “gamer-ness.”

A game doesn’t have to be easy. Many games such as chess, which you mentioned, or baseball, are very difficult. They are not the kinds of things that you just step up to and succeed at. Many video games are similar. They require that we learn their rules, understand their rules, and understand how to use the abilities we have access to. We use all of this to solve the problems that the game presents to us.

If you understand what is required and you enjoy that sort of thing, then you will play the game. When you mess up, you will understand that the game is not attacking you; the game, after all, is a clockwork device that you have complete control over. When you hit your knee with a boomerang, it is not the boomerang’s fault. The boomerang is not being mean to you. If you learn to use the boomerang, you can have a lot of fun with it, but unless you adequately realize where the issue lies, the problem can never be solved.

That is not to say that the player is always the problem! There are certainly many games that expect far too much from their players, or are riddled with frustrating bugs. But if a player does not come to the table ready to learn, willing to push themselves and experience something new, then they have chosen for themselves to close the doors leading to many fantastic experiences and opportunities.

That being said, I think it’s a quite unfair to say “Braid is not a game.” Why attack Jonothan Blow for not catering his game to your specific desires?

I wasn’t attacking him. I was asking a question. And trying to make a point because many people are not sure whether our games at Tale of Tales are really “games”. And they have a point, in some respect.

But in some other respect, you can also question whether Braid is a game. Or most computer games, even. Which is what I did. It doesn’t really matter what your personal definition is. Because it’s wrong. It’s wrong because, as Wittgenstein points out, the word game has been used for many different things that do not share a single common element. Ergo: there is no definition of “game”. Not one that can cover all things we, humans, have called “game” throughout history.

Anyway, you do have a point that to play a computer game you have to be ready to fail and repeat and learn the specific skills required for that game. But I don’t think not being interested in that sort of process in computer games makes us, the majority of the population on this planet who does not play these games, somehow handicapped or stupid.

I think people have the right to not want to play the kinds of computer games that currently exist. Computer games are not a religion that everyone needs to be converted to. Or a scientific theory that we all should believe and accept as the truth. Computer games do not make everybody happy. Just a small portion of the population that likes that kind of activity.

My only real point is that computer games only cover a very small part of the range of activities that have been called games before. And I wish they’d cover some more.

I hope I never implied that not being interested in a particular kind of game makes someone somehow inferior, because of course it doesn’t. It would be stupid and myopic to suggest such a thing.

I agree with you that video games as we know them have only scraped the surface of the full potential of the word “games”, and I am very interested in gradually watching that potential be realized.

In a previous post you wrote about how you don’t enjoy any recent games for similar reasons to the ones you cite here. But you wrote that you enjoyed Ico and Tomb Raider, two games which certainly punish you for failure (often with the death of your avatar) and which require you to understand complicated controls and goals. The apparent inconsistency in your position irritated me for a while.

But I now see that you are simply focused on enjoying a very particular aspect of games. In writing a fanmail to Derek Yu recently, (about his game Aquaria) I wrote this:

“I think the expansive world gives your game that X-factor that few indie titles have… we don’t really have a good word for it but it is something like ‘evocative’ or ‘romantic’ (in the strict sense of the word) or ‘wonder’. Michael Samyn says that he loved Ico and Tomb raider, but dislikes just about every other game, and I didn’t understand that until I figured out that he is looking for this quality in games – with ‘The Endless Forest’ they had the right strategy, but not enough content. I think that by producing such an incredible amount of content, you imparted Aquaria with that feeling of wonder which is missing from so many new commercial games, where the vast bulk of development resources go into producing realism which is detailed and cramped, which creates a world which feels like a tiny vignette or a movie set.”

This is how I made sense of the apparent incompatibility in your views – when commercial games were too visually and sonically crude, it was hard for them to evoke much wonder in the player. After a while, they became richer, and some games came out which had this quality in abundance. But now the expected level of quality is *too* rich, meaning you get small amounts of very detailed content, with which it is much harder to evoke a large universe. This is why ‘Ico’ might have this quality, while ‘Gears of War’ might not.

It’s worth pointing out that Jonathan Blow, by contrast, has a goal in mind with his game that is completely orthogonal to this. He is interested in exploring every conceptual implication of a core game mechanic. He is interested in giving the player a moment of cognitive epiphany (and I think he succeeds at this in Braid) I don’t know if this is true or not, but I predict he would find ‘The Endless Forest’ completely void as a gaming experience.

For my part, I think both of you are wrong to discount the value of the other dimension. Just as art can be many things and serve many purposes, so can games. It’s not true to say everything is a game, yet it can be true that many disparate things are games. My favourite games combine challenge, and narrative, and epiphany, and wonder.

You said:

“It doesn’t really matter what your personal definition is. Because it’s wrong. It’s wrong because, as Wittgenstein points out, the word game has been used for many different things that do not share a single common element. Ergo: there is no definition of “game”. Not one that can cover all things we, humans, have called “game” throughout history.”

What Wittgenstein has said is clever and insightful, but it is far from the be-all, end-all truth. One of the things that makes humans so powerful is language. Using language we can describe anything we wish to; there is nothing that language cannot describe. To suggest that there is no definition for what constitutes a game is simply giving up.

You’re right Bennett, about what I find enjoyable and motivating in a game. I agree in principle that games can be many things simultaneously. But in practice a) extreme challenge often makes it impossible for me to access the other side of a game and b) there are very few games that don’t have challenges, so as long as there’s nothing to compare to, the possibility remains that games without them are superior.

They are likely to be superior for you, I agree. For me, I’m pretty sure they would be inferior. Anyway, I agree that it’s worth trying to make some, if only to see if the audience exists and if the concept works. I would predict that there are a lot of people like you who would appreciate such games (my wife would be one, for example).

For my two cents, you should head more in the direction of ‘Endless Forest’ and less in the direction of ‘The Path’, if you are really trying to capture this particular dimension of enjoyment. Not that I don’t see the value of these interactive storytelling games – but I don’t think it’s the right way to create games that are imbued with that quality you are seeking.

I just played Braid for the first time ever. I was with a friend who had beaten the game and he was able to get me through the really tough puzzles. We beat the game in about an hour and a half. My initial opinion of Braid was that of genuine interest I thought it was beautiful and the game play was engaging. After beating the game, watching the game get beat, The ending raised the Braid from a simple game to art. What a psychological thriller1

Ummm… Too pretentious in my opinion. I dont mean to be rude, I really respect your work and your personal, alternative vision, but… Millions of people enjoy conventional games (including myself) but because YOU dont like it, you say that games are wrong designed, or maybe games are not games at all… Everybody is wrong?

Please don’t take the stream of consciousness above as any sort of statement! It is nothing more than a series of questions.

Design is very simple to judge. Because it has a purpose. If the design does not meet its purpose, it has failed. A ladder is a great design. For people who have legs. A handle is a wonderful way to open a door. If you have hands. Written instructions are great. If you can read. Etc.

(Ah, sorry about my english!)

There’s one BIG mistake in this little essay: you CAN’T fail in gravitation. There’s not really a challenge, just different ways of interaction: you can just pass the time with the girl (then she’ll never leave); you can follow your “ideas” (taking the stars), but then you’ll be alone. You can take one star at a time, burn them (work your “ideas”), or chase them all – and they won’t give you much “points”. But you can’t just fail, it’s impossible to fail in this game. Each way of interaction leads to a different output.

In another note: I’m impressed knowing you have ever played a game designed by Jason Rohrer, since in my opinion they have just what is missing in Tale of Tales’ games: the gameplay is what is symbolic, not a bunch of non-interactive cutscenes. They are art because they are games, they can’t be another thing. “The graveyard” just ignores the existence of the player for most of the time: it’s more a short-movie than an interactive art. In my opinion, it would be BETTER being a short-movie than a game. Same with “The Path”. I think it’s a wrong direction to “art” games – since it ignores the potential of the media. What is symbolic in The Path and The Graveyard are the non-interactive parts of the games; in Gravitation, Passage and Between (all designed by Jason Rohrer), your actions (as a player) are the symbolic part of the game; is what you do, not what you see what is interesting. Then, these games aren’t just “tests” – there’s no right or wrong answer, but an interactive environment in wich your actions can have various meanings. You should really play these games again, read the “author statement” written by Rohrer (it’s not needed to play, but is a nice insight into the way the games were made), and maybe change your view.

In The Path, we really have a test: the game says if we won or lose. And it’s not even in an ironic way – it’s too straightfoward. You didn’t did what the progamers intended (don’t stay on the path), then you lose. I was expecting more from an “art game”. Much more. Still, I think Tale of Tales’ work is important in some way – even if it’s important just because the discussion they’re provoking. But they really aren’t a good example of “art games”.

Just a further thinking: what is the “test” in Passage? What is the “test” in Gravitation?

Cerv, I’d encourage you not to generalise your own opinion. Many people agree with you. Which is part of the reason why we are trying to do something else. But many people don’t agree with you either. I think there is no right way and no wrong way. Just different ways for different people. Some people like the clear rules-based symbolism of Jason Rohrer and Rod Humble, other people like the vague introverted ambiguity of our own work.

I agree that we use interaction in a different way. But I disagree that The Graveyard or The Path would have been the same as movies. Saying that really shows that they are just not for you, that they don’t fit your mindset or cultural background. And that’s ok. Different people like different things. Different people need different things.