We were pleasantly surprised by Frank Lantz‘s brief presentation at the last GDC. Especially because we found ourselves agreeing with somebody who was saying the exact opposite of what we are always going on about. We always argue that videogames should differentiate themselves from traditional games and cast off the heritage of rules and goals in order to develop into a new artistic medium. But Mr. Lantz claims that videogames are not a medium at all and should not aim to become one. Instead he encourages designers to focus much more closely on the rules and goals of their work and get (back) to the essence of playing games. We agree that this is the best choice for many videogames, if only because they’re not very interesting in terms of narrative and immersion anyway. Their strength simply lies elsewhere.

Frank Lantz makes a convincing argument for the great potential that games-as-games continue to have.

Games are not media

“Eventually we’re going to stop thinking of games as things you put into your computer and start thinking of computers as something you put into your game.”

Tale of Tales (ToT): You are well known for having said that games are not media. Could you explain this a little bit? And how do you think current videogames are doing in this respect?

Frank Lantz (FL): There are certain connotations to the word media that I would like people to question when it comes to games. So really, the slogan “games are not media” can be broken down into these four smaller claims, which are maybe more understandable:

- 1. Games are not some totally mysterious, new-fangled form of McLuhan-esque electro-culture. The idea of “games as media” reinforces the conceptual gap between video games and the long history of play that predates them. It’s what allows us to say “games are still in their infancy” as if adding computers to something is an excuse for making it worse. If we want to make better games we should understand video games within the long history of traditional games and play (which is still plenty mysterious!). We should claim this as our heritage, proof that games are here to stay. Computers have their roots in games. Games were here before computers and games will still be here after computers are gone.

- 2. Which leads directly to connotation number two – that video games are media, because they’re something you play on a computer. They fit into a computer or a console the way a DVD fits into a DVD player or the way a TV show fits into a Television set. But I think this view reflects too strongly our particular historical circumstances. To us, computers are new, they’re big, cool, interesting objects. But eventually computers as interesting objects go away, because what’s really important is not computers per se, but the things they do – computation and connectivity. Eventually we’re going to stop thinking of games as things you put into your computer and start thinking of computers as something you put into your game.

- 3. The next connotation of “games are media” is that games are chunks of content that I consume. And, yes, lots of games are like this, many video games are chunks of content that I consume, but not all of them. Many games are more like habits that we weave into our daily life, languages that we learn, clubs we join, practices that we become proficient at, a part of us not for 5 or 50 hours, but for our entire life. And all games are a bit more like this then we might normally think.

- 4. Finally, games as media strongly implies a certain way of thinking about how games are meaningful – what I call the “message model of meaning”, ie. that you have a speaker over here and a listener over there and the game is a conduit that carries the message from the first to the second. I think games are much more complex than that. They’re like meaning networks, little non-linear meaning-generating machines. The hard (and fun) work is figuring out how they mean, and how to make them richer and more meaningful, without resorting to old-fashioned ideas about messages and media.

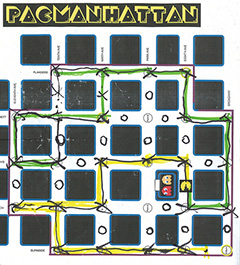

“Pac Manhattan” was a game played

on the real city streets.

ToT: Do you see a difference between videogames and other games? If so, what? And do you think it’s a good idea for this difference to increase or should videogames get closer to other games?

FL: Yes, there is a difference. And sometimes I like to stop and remind myself that this difference might be bigger than I think. It’s possible that video games are some totally new form of culture that are only related to, say, Golf and Poker by a quirk of history. Maybe the truly interesting and beautiful and meaningful aspect of video games are the immersive real-time 3D environments and interactive narrative. This is, if I understand it correctly, sort of ToT’s view of the situation. And I’m willing to believe that it might happen. Maybe 3D video games will evolve into immersive, interactive, real-time story-spaces without the competition, challenge, and winning and losing of games. It’s possible. But I don’t see a lot of evidence of it. I don’t see a lot of promising embryonic examples of this type of thing, I don’t see a ton of green shoots in this direction. For me, personally, the most interesting and successful video games are the ones that share the traditional fundamental qualities of games. Immersive environments and real-time 3D are spectacular and revolutionary new ingredients, but I don’t see them taking over and replacing everything else. Because the everything else is also pretty spectacular: the beauty of non-linear dynamic systems, stylized social interaction, the alchemical transformation of violent impulse into articulate complexity, collaborative exploration of possibility spaces, madness and randomness dancing with logic and structure, these are the things that I love most about video games and they’re also at the heart of games in general.

“We should strive to make games that are worthy of all the attention and passion that humans pour into making and playing them, games that move us and bring us exquisite sadness and overwhelming joy … Is that art? Who cares?”

Art & Aesthetics

ToT: There’s a certain desire for videogames to become more artistic. At Tale of Tales this leads us to move away from the formal structure of rules and goals. But other designers (most notably Rod Humble, Jason Rohrer and Jonathan Blow) insist that the artistic expression should happen through this language of rules and challenges. Do you think games can be art? Should they be?

FL: To me it’s simply obvious that games belong to the realm of aesthetics. Games are something we do for their own sake, they provide complicated and interesting and rewarding emotional and intellectual experiences. We find some of them fascinating and moving and compelling and meaningful and some of them less so. And the things that make me prefer Crackdown to GTA or Poker to Chess or Cave Story to Castlevania are ineffable, they’re a matter of opinion, style, politics and taste, something to argue about, discuss, and consider but never fully resolve. And all these qualities are the hallmarks of aesthetics. The word “art” is tremendously divisive and confusing, it’s like dropping a little confusion bomb into the conversation. Instead let’s say that whatever we find interesting and rewarding about games, we should be striving to evolve and make deeper and richer. We should strive to make games that are worthy of all the attention and passion that humans pour into making and playing them, games that move us and bring us exquisite sadness and overwhelming joy and give us fascinating things to think about and talk about, games that freak us out and challenge our standard ways of thinking and acting and blow our minds, as well as games that comfort us and amuse us and hypnotize us and devour our time. Yes, let’s make games that can do all these things in new and surprising and old and familiar ways. Is that art? Who cares?

ToT: But aesthetics is usually not the most important aspect of art that the people trying to make art with games are concerned with. They are concerned with expressing ideas or, as in our case, creating tools for exploring ideas. It’s not only about experiencing something beautiful, but also about communication, and thought about relatively specific subjects.

Do you think it is appropriate to use games for this?

FL: When I say aesthetics, I meant to include all the various permutations of idea expression and idea exploration that you talk about. It’s funny, because I say “aesthetic form” to avoid using the term “art” with all of its confusing, complicated baggage, but of course “aesthetics” can be just as confusing, for many people it implies visuals specifically or the notion of beauty. Suffice to say, I think games can and do explore and express ideas and address subjects, of course!

Games & Play

ToT: We often feel that videogames are a lot more strict than many of their analogue counterparts (especially children’s games or other more physical and social “body games”). Which leads to the odd contradiction that videogames don’t allow for much playfulness. Do you find this evolution interesting?

Ads for “Chain Factor” wove

the game into your daily existence.

FL: Yes. I think games are full of these kinds of contradictions and paradoxes. Constraints and freedom, determinism and randomness, obedience and improvisation. I think the really interesting stuff is the dialectical dance between these forces, not in the victory of one over the other. It’s not a race, you know (LOL).

ToT: Steven Poole has remarked that videogames these days resemble work more than they do play. Do you agree? Is that a problem?

FL: The relationship of games to work is super complicated. I guess I would have to say I don’t agree. Does gem crafting resemble work? Of course it does. So does tossing the caber! Let’s just say these things resemble work in an ambiguous, through-the-looking-glass way.

ToT: Most videogames are single player games. Most non-computer games are multiplayer games. How come?

“LEGO Junkbot” made by Gamelab

FL: Hm. That’s a really good question that I never thought to ask. Maybe the presence of other human minds and wills is an essential ingredient in making analog games produce deep, interesting, surprising, dramatic situations. But software can produce those kinds of situations without other humans in the loop. And doing things that require other people can be a pain in the ass. So that seems like it could be one factor.

ToT: Non-computer games, which are most often multiplayer, can be won or lost. And the losers complete the game as much as the winners do. Only with a different outcome. Many videogames, especially single player videogames, need to be won to be enjoyed. Losing is often simply the failure to complete the game. And you are encouraged to start again. Until you win. What do you think about games that cannot be lost?

“… the beauty of non-linear dynamic systems, stylized social interaction, the alchemical transformation of violent impulse into articulate complexity, collaborative exploration of possibility spaces, madness and randomness dancing with logic and structure, …”

FL: I would say the tension between success and failure is a key ingredient in all games. But I think it’s possible you can make things that aren’t games, but are other kinds of expressive, meaningful interactive systems. I’m eager to see more of the kinds of work that ToT makes, interactive narrative environments, whether they’re games or anti-games, it’s a direction worth exploring.

ToT: I wasn’t referring to our own work, or any other concepts of “non-games” or “anti-games”. I was referring to virtually all mainstream videogames, especially of the action/adventure variety. They tend to be very linear and the only losing condition is failure to continue the linear thread.

As opposed to more traditional games (football, chess, board games, etc), where one person or team wins and the other loses and that’s the end of the game for everyone. Many videogames don’t allow for loosing to be the conclusion of the game. You have to win. If you haven’t won the game, you haven’t really played the game.

Any thoughts about this difference?

“Drop 7”

FL: I think maybe this is a result of the difference between multiplayer games and single-player games as opposed to a difference between video games and more traditional games per se. Also, I would note that sometimes you can take a single-player action/adventure game and look at it as a game system, where the overall game experience is actually made up of a series of more or less discrete encounters each of which looks more like a traditional game. Each of these discrete encounters has a quantifiable outcome, where I win or lose (or win to a greater or lesser degree according to how much health/ammo/other resource I have left at the end). JRPGs are very much like this. Although I know beforehand that my eventual progress to the end of the game is assured each battle provides a certain amount of the uncertainty necessary for something to be a game.

ToT: Can you tell us a bit about what you consider to be the greatest game projects you’ve worked on so far? And what you’re working on now or will be in the near future?

FL: I am inordinately, unseemingly proud of almost every game I’ve ever worked on, but I don’t know if I would call any of them “great”. PacManhattan is probably the most famous game I’ve been involved in although only a small handful of people ever played it. I think the Big Urban Game was pretty great. I’m very proud of Drop7 which is a small, abstract game, and Chain Factor which is the giant, sprawling, interactive narrative that spawned it. I’m proud and a little shocked by the amount of time and affection that players have poured into Parking Wars on Facebook. I’m still especially fond of the Junkbot Lego games I worked on at Gamelab and of Ironclad, the boardgame I designed for the book Rules of Play.

The things that I’m working on now I can’t talk about yet.

ToT: I had no idea you were involved with Junkbot. My kids loved that game!

Thank you so much for illuminating your fascinating thoughts. Let’s hope they will be infectious. You almost had us convinced! 😉

Interview conducted via email by Michaël Samyn in April and August 2009.

Then you are blind, Mr Lantz. Video games are filled with examples of this! Almost every commercial game is a demonstration of the immersive and narrative power of realtime technology. It’s true that most video games still have a game as their backbone. But that’s just a detail. It may go away. Or it may not. What matters is the other things that happen. And sometimes videogames, even today, allow us to enjoy them, despite of the game structure (or in rare cases, the game structure contributes because it happens to be a story about conquest or another game-related theme).

At Tale of Tales, we may be a bit too extreme in our desire to remove gameplay as much as possible. But I’m sure that in the next generation of video game designers, there will be people who will solve this problem. And then video games will become a true medium that will rise above its current status of comic book equivalent and rival literature, theatre and cinema.

That doesn’t mean that games are not a perfectly fine thing to make and play. It just means that something new has entered the world. And it’s fascinating!

Michael,

You said, ToT tries to “remove gameplay as much as possible.”

Correct me if I’m wrong, but in The Path, you do have traditional game rules. I “failed” one time because I didn’t collect enough objects. I wasn’t even told I was supposed to do that. I was so angry and disappointed I never played it again.

We use traditional game rules where it feels appropriate. We just don’t feel obliged to include them in our designs.

As for The Path, actually, you didn’t fail because you found too little objects. You failed because you obeyed your mother’s command (“stay on the path”) and this is not how the story goes. You failed to tell the story. Collecting is a completely optional activity in The Path.

Michael, doesn’t the fact that something is a “backbone” indicate that it’s more than “just a detail’?

Also, I would point out that Tale of Tales most successful release, The Path, is also your most ‘game-like’, with puzzles and goals and winning and losing. How do you explain that?

Not if the backbone pushes something to take an awkward shape. In the case of video games, the game backbone forces games to be linear, for instance.

The Path was designed to be as successful as possible. I agree there is some merit in appealing to a big audience. But public success is by no means a proof of artistic quality.

More importantly, though, I think we need to experiment with this new medium. I understand that being conservative is somewhat trendy these days. But I think it’s a shame and a waste that we keep doing the same old thing over and over again instead of exploring the enormous new potential that this medium is giving us. Obviously exploration experiments will not be as successful as products that re-use conventions. But that shouldn’t stop us.

I believe that there’s something out there that is huge. And we won’t find it by running after our own tails.

Could you define how you’re using the word ‘linear’? From where I’m standing it’s games that have the reputation for being non-linear (what with all that ’emergence’) while most other forms of art are either linear or static. It’s the effort to make games resemble other kinds of art forms that has made them more linear.

Also, what evidence do you have that there’s no experimentation going on in games? I hear this phrase thrown around a lot, usually by people who are only paying attention to what’s being released on the consoles. There’s much more going on than just what appears on the major platforms.

Linearity was just an example. You’re probably right that it’s often included through imitation of other media. Though the very notion of winning and losing already implies linearity.

I’m afraid games as such don’t interest me much, experimental or otherwise. I’m more interested in what else can be done with the interactive medium.

You haven’t really answered my question and defined exactly what you mean by ‘linear’ or ‘linearity’, so I can’t really respond to you. I will say though that we clearly mean different things when we use those words.

You also didn’t answer my question of why you claim there’s a lack of experimentation in games or interactivity in general.

Anyway, it’s fine to not be into games, but if you’re interested in interactivity you MUST be familiar with them. Games are one of our oldest forms of culture; they’ve been dealing with interactivity in more depth and for longer than anything else.

I don’t like defining terms because then the discussion switches to a semantic one of which the only purpose is for someone to “win” over somebody else. And you may have gathered by now that winning (or losing , for that matter) is something I’m not into either.

Instead, allow me to be fascinated by the diversity of meanings that humans give to words. I wouldn’t want that to go away.

I’m not sure if, at the end of the day, I’m interested in interactivity as such. I like how a computer can do things and a person can do things together with a computer. I like how fiction and reality melt into one. The player does something and the computer interprets it and does something back, etc. I like this kind of conversation with a story.

I don’t particularly like playing games with a computer. I think humans are better at that. Playing games with humans is much more fun.

This isn’t about winning or losing, it’s about having a fruitful exchange, which can only take place if the participants are willing to clarify what they actually mean when they say something. I’m not trying to threaten the “diversity of meanings”, I’m just asking what you meant when you used this specific word in this specific instance. Maybe you didn’t mean anything in particular, which is fine, but simply say so.

For example, I can gather from your response that you associate the term ‘interactivity’ with computers. This is fine and I think is actually a widely held association. I happen to not agree with it. I think that all games are interactive systems whether they’re governed by computers or human beings.

Which brings me to my original point that if you’re interested in rule based interaction between human beings you have to look at games, because they’ve been dealing with it for several thousand years.

And we can have a discussion about that, and exchange ideas, because now we both know what each one of us means when we use that word. So I guess I’ll ask again, because I’m genuinely curious, what did you mean when you said “In the case of video games, the game backbone forces games to be linear…”?

I’m not so interested in the interactivity between people. At least not in terms of designing that interactivity. But I am interested in interactivity between humans and computers, or more broadly, between humans and what computers can present (stories, images, sounds, etc). I am aware of the fact that games are ancient. This is one of the reasons why, as a designer, they don’t interest me much. As an artist, I have nothing to add to chess. But the computer still holds a lot of potential for me.

I think games, as an ancient form, are not the ideal vehicle to research the potential of computers. The risk exists that we get stuck in perfecting game design as such, with the aid of computers, and not go beyond that and find out what else, what new the computer can do, in terms of entertainment and art. That’s what I mean when I say that games are holding back the medium, or that they force certain formats (such as linearity).

I agree that games are a field worthy of study. In and of themselves and with relation to designing interaction with computers. All I’m saying is that we should not stop there. There’s many other fields that can be equally inspiring when designing interaction with computers.

I’m playing Drop7 at the moment. It’s brilliant!

But why am I playing Drop7?

I have an urge to play it, I’m amused while I’m playing it. But when I stop playing, it leaves me feeling empty inside. And sorry about the time I wasted on it.

And now I find myself actively resisting, refusing to play Drop7. In favour of doing nothing, just lying in bed, looking around.

I enjoy Drop 7, I think, because it makes part of my brain do things that it likes to do without having to think about it much. But, unlike doing nothing, it also seems to actively prevent thinking. This is how I end up feeling empty inside after playing.

Other sorts of entertainment not only require me to think but they stimulate and trigger all sorts of thoughts, that may or may not have anything to do with the game/painting/novel/music etc. And that’s how I end up feeling full afterwards, not empty.

Hi all

The idea of games PREVENTING thinking is a provocative statement. It isn’t a statement that feels true, however; more likely this is a reflection of the kinds of thoughts that you personally find valuable or interesting. I’m not sure that it is fair or wise to claim that thinking about the most efficient way to break some circles in drop7 is somehow less valuable than thinking about the latest adventures of Sasha Cohen, or attending a performance of Petrushka.

Personally, the glassy-eyed stare of the tv or movie viewer lulled into a childlike state by the expert use of timing and musical queues makes me far more uncomfortable. Maybe it’s simply an illusion created by the fundamental differences between passive vs active entertainment/art/whatever.

All that said, I too find myself wishing I could have those dozen hours back that I spent on a not-so-rewarding game (although not in the case of drop7!). However I also wish I hadn’t bothered to watch movies such as AI, or read books such as The Count of Montecristo.

I think I agree that it’s a matter of value that one attaches to certain types of thought. I’m also vaguely reminded of my personal dislike of mathematics, while other people consider mathematics to be very meaningful and deep. The pleasure that mathematics gives to those people seems similar to the pleasure people get out of interacting with game systems.

Agreed, I think that makes sense. I also feel that there is a strong similarity between listening – and performing – music and the kind of thinking produced by games such as drop7. Both feel fundamentally abstract or unknowable to be in an interesting way. They are able to exist outside of language in a way that movies and books cannot, or at least tend not to be able to.

Maybe that’s why I like ’em!

Hm. Music is rarely abstract for me. A single note can be enough to bring me to tears. Music is linked so closely to emotions. The sound of a certain instrument expresses the atmosphere of that instrument’s origin and place in history. It’s almost overwhelming how much information music contains. Math or abstract games seem very barren compared to that, for me.

Well, I certainly agree that music is more adept at plucking our heartstrings than a game, abstract or otherwise! I don’t feel that abstraction is antithetical to emotion, though… I find certain music deeply moving but difficult or impossible to explain, even with the ability to analyze its most basic elements via a score or computer-aided spectrum analysis. To me, abstraction has less to do with quantity of information and more to do with a lack of specificity or meaning…

It’s true that instrumentation and (of course) lyrics can carry a lot of information about the origin or intent of a piece but, personally, that kind of information tends to have very little to do with the reasons I care about music. For example, I enjoy Gagaku, ancient japanese court music, because of the spooky, other-worldly instruments and glacially slow pacing, not because I’m especially interested in ancient japan.

By the way, thanks for indulging me in these tangents!

And you me. 😉

I didn’t mean to say that abstraction is antithetical to emotion. Just that music, and sound in general, often carries a lot of information, that may or may not trigger emotions. The abstract, by definition, does not carry such information. The abstract can rarely be described as “spooky” or “otherworldly” for instance. I think some people enjoy abstraction a lot. I tend to prefer the anecdotal.

Michaël, just so you know, your three comments starting with “I’m playing Drop7 at the moment. It’s brilliant! :)” read like one of those awful character logs that get strewn everywhere in FPSes.

I’m not sure I’m familiar with these logs, David. Is it a new form of literature?

Whoa; huge diss on Alexandre Dumas! That’s not cool!