It is difficult for us the express in words what we are trying to do with our creations at Tale of Tales. We call them video games, but we are well aware of the fact that we are stretching the meaning of the term when we do this. We continue, however, because, for us, the meaning of this term has already been stretched. Perhaps not by the way that video games are being designed, but definitely by the way that they are being played. By people like us.

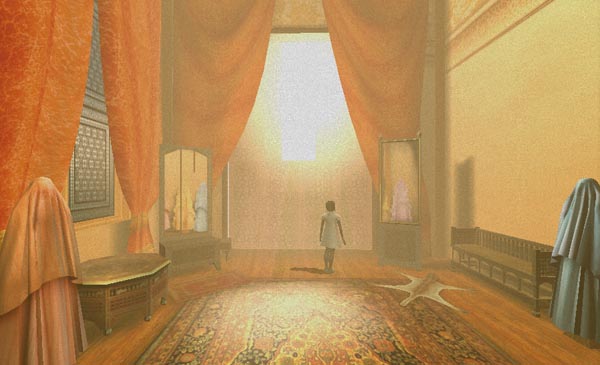

The medium that is used by games -realtime 3D- is attractive to us as artists because it is a powerful tool for simulation. So far, game technology has been mostly used for simulation of objective factual reality. But we are interested in using it to simulate a subjective reality.

Many of our ideas originate from a question in the form of

“What would it feel like to be creature x, doing activity y, in location z?”

Our designs often start as an attempt to find the answer to this question -although they may outgrow this initial empetus later. Not by showing how it feels to be x, doing y in z, but by creating an environment in which the user can, if not experience the sensation itself, at least contemplate the experience by themselves.

We share this purpose with many artists, throughout the ages. Baroque composers, renaissance painters, romantic poets, all have similar aspirations. But their work relies entirely on the imagination of the viewer to create the effect. The interactivity of computer technology allows us to give the user a more active role in the piece, which we hope will stimulate the imagination more than mere observation. This is how interactivity becomes a crucial part of our work.

We don’t think we are the first designers to use the medium in this way. Many video game designers have and do. But creating the sensation of “being x, doing y in z” is most often of less importance than the fact that the end product needs to be a challenge-based, entertaining game (or a clear plot-driven narrative, for that matter). There are various reasons for this, both economic and artistic. But as players of video games, we have often been disappointed when our experience was interrupted by the requirement to play the game (or progress in the story). As a result, as designers, we try to create games with the tables turned: simulation becomes more important than gameplay, meaning becomes more important than fun (and sensation more important than communication).

We have probably made the mistake in the past of presenting our personal choice as something that the video game design craft as a whole should aspire to. That was wrong. To us, as video game consumers, moving away from challenge-based entertainment-focused gameplay towards poetic and meaningful experiences, feels like progress, simply because this leads to an increase in the offer of games that we enjoy. But is not progress in any absolute sense -unless you consider greater diversity a form of progress.

There is nothing wrong with games that offer fun and entertainment. There is nothing wrong with games that try and evoke meaning through gameplay. Games have been around for ages. They will never become obsolete. It is naive to think that they will ever turn into something else. And it is naive to think that anything threatens their existence. But computer technology was not invented for the sole purpose of creating and playing games. And to consider video games as the ultimate form of interactive entertainment or art, is simply premature and unnecessarily restrictive.

At Tale of Tales, we are not interested in creating challenging skills-teaching gameplay with rigid rules and predetermined goals. We may use these kinds of structures in our work if they contribute to the sensation of “being x, doing y, in z”. Some themes are served by this, some are not. But we feel no obligation whatsoever as designers to include such forms of interaction in our work.